Experts say rules to protect workers aren’t enforceable. Advocates and unions are fighting for an emergency safety standard that will last through the pandemic.

In the three months since Covid-19 was declared a public health emergency, workers have filed 4,775 complaints to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), many alleging that their employers failed to provide the necessary personal protective equipment needed to protect them from the novel coronavirus. But only one complaint to the federal agency, which is in charge of assuring safe and healthy working conditions, has led to an official citation—that, to a Georgia nursing home for improper recordkeeping.

Workers in many sectors of the American economy, from the frontlines of the crisis, to those whose jobs—until three months ago—were essential to our everyday lives, but not necessarily to our very survival, have performed their duties where social distancing is nearly impossible. Thousands, if not tens of thousands, of workers in America’s meatpacking plants have tested positive for the virus. And just this week, public health officials in California reported a spike in infections among grocery workers.

So why hasn’t OSHA done more to protect them? Experts say it’s because OSHA, like other agencies tasked with ensuring our health and safety, has been deregulated over decades in order to give employers more control over workplace oversight. The agency issues guidance, but permits employers to enforce those rules and hold themselves accountable. That long-running effort has been hastened by the Trump administration during this pandemic. Now, workers have little recourse to hold their employers accountable if they believe they contracted the virus while on the job without adequate protection.

“There are thousands of complaints that have been filed, and in quite a few of them, the agency has said, it appears the employer is doing okay.”

“This is a pretty unfamiliar situation,” said Susan Schurman, former dean of the Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations.

An April 10 memo posted online showed that OSHA’s coronavirus strategy had been to focus on industries it considered “high risk”—like hospitals, emergency response, police, firefighting, and prisons. In that same memo, the agency announced that all other employers would not be required to record cases where workers had tested positive for Covid-19, unless there was “objective evidence” the infection was work-related. (That term of art was not defined.) The move, the agency said, was to “help employers focus their response efforts on implementing good hygiene practices.” (The agency has since backtracked and began requiring records again on May 19.)

Three days later, OSHA announced that it would not conduct on-site inspections of “medium” or “low risk” workplaces, like meat plants or grocery stores, where workers had filed complaints.

As a result, daily inspections plummeted. On May 18, one day before the agency reversed its decision, Politico reported that OSHA had inspected fewer than 8 percent of 3,990 coronavirus-related complaints the federal agency had received since March. In many of those complaints, workers alleged that employers didn’t provide masks and gloves, forced them to work with people who appeared sick, and couldn’t maintain six feet of distance in cramped work spaces.

As of this writing, the agency’s federal and state branches combined have received 16,360 total complaints, closed over 10,000, and inspected only 253, according to a Covid-19 section of its website. At a Congressional hearing, Loren Sweatt, the agency’s acting director, said the agency wasn’t inspecting cases because most would not withstand court scrutiny, and would act on the others within six months, according to a Law360 report.

“Covid-19 has caused more deaths among workers in a shorter time than any other health emergency OSHA has faced in its fifty-year existence.”

Those numbers don’t surprise Rip Verkerke, director of the University of Virginia’s employment and labor law program. Despite thousands of complaints, he says the federal agency has only issued a single citation in part because there’s no coronavirus-specific safety standard to be enforced. A “general duty” clause, which requires employers to clear workplaces of hazards that are likely to cause death, is hard to enforce.

“There are thousands of complaints that have been filed, and in quite a few of them, the agency has said, it appears the employer is doing okay,” Verkerke said.

OSHA has issued industry-specific safety memos and suggestions to employers, which are non-binding. That approach, which deprioritizes enforcement, is typical of the agency under Republican administrations, Verkerke said.

But advocates say guidance isn’t enough, and want the agency to enact an “emergency temporary standard” that would require employers to make changes to the workplace or face fines. In a lawsuit filed last month by the AFL-CIO to force that standard, the labor union said such a standard would prevent more essential workers from being exposed to the virus on the job.

“Covid-19 has caused more deaths among workers in a shorter time than any other health emergency OSHA has faced in its fifty-year existence,” the petition read. The agency’s failure to issue a new standard is “a stunning act of agency nonfeasance in the midst of a workplace health emergency of a magnitude not seen in this country for over a century.”

Nellie Brown, who directs the occupational health and safety program at Cornell University, says the threat of citations, whether in the form of fines or public notice, can motivate employers to make safer workplaces. She agrees that coronavirus poses an imminent threat, and warrants a stronger response from OSHA.

“In so many places, people have not looked at the workplace through the lens of communicable disease. These are huge changes that have to be made.”

A “good faith” effort to reduce exposure isn’t enough. An emergency standard, which would set temporary rules for six months, before permanent rulemaking around airborne transmission, would save lives.

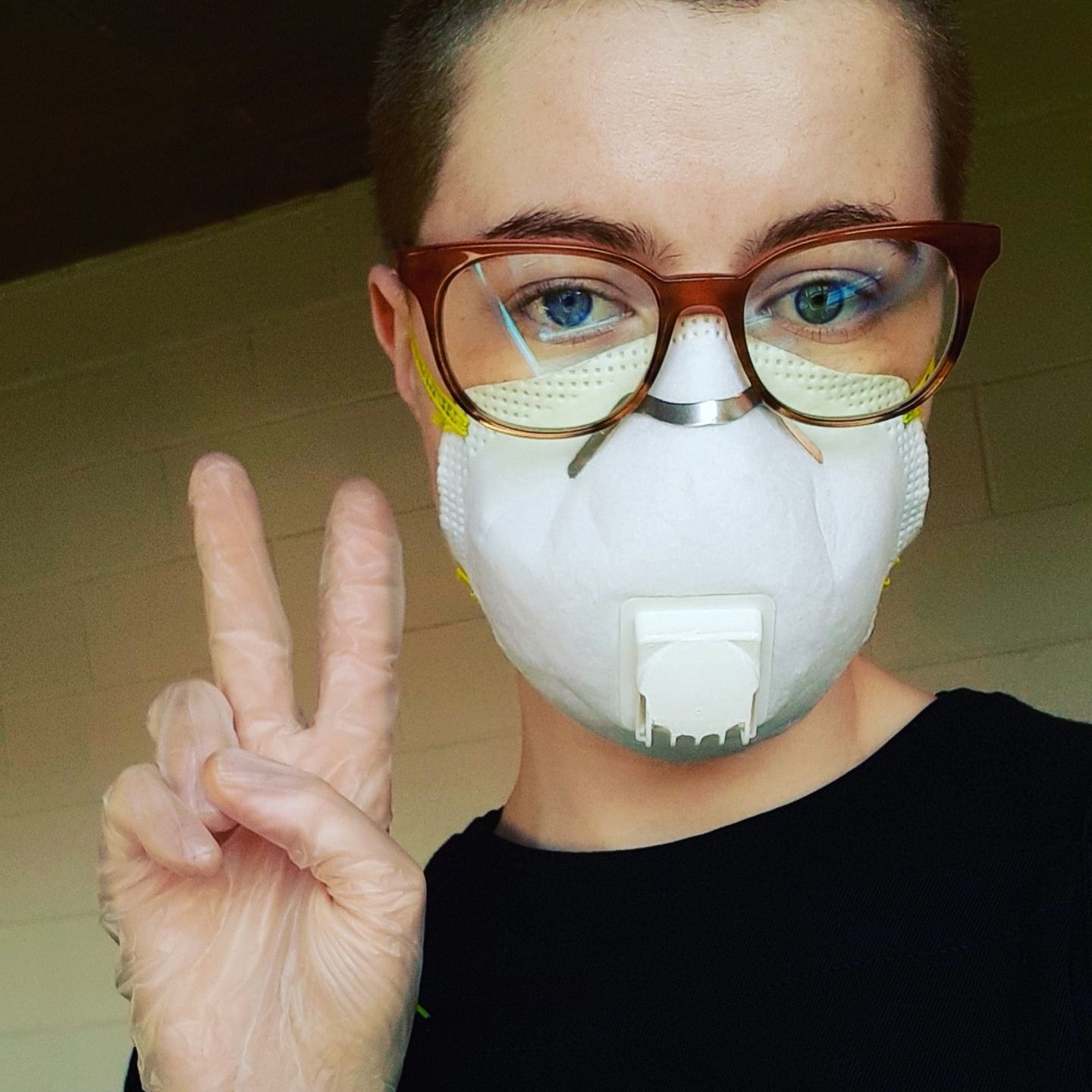

“The problem is, even if you make a good faith effort, can people even get the stuff they need, like N95 respirators?” Brown asked. “In so many places, people have not looked at the workplace through the lens of communicable disease. These are huge changes that have to be made. It’s very hard to go back and say that, but that’s the issue.”

In the absence of those rules, what recourse do employees actually have? “None,” said Schuman, the former Rutgers dean. There are other options available to workers, she said, like suing employers for damages, or going on strike if they’re in a union. But those efforts aren’t likely to succeed during a national emergency, because a judge would reject the case, or the federal government would force workers to return to the job.

The lone citation continues to disturb not only Democrats and labor unions, but even the agency’s own watchdog. The Labor Department’s inspector general will issue a report on OSHA’s coronavirus-related enforcement later this month.