The title The Memoirs of Wendell W Young III: A Life in Philadelphia Labor and Politics, about as straightforward as one could wish, gives an indication of which readers might be most interested by this book. As a history of unions, this is an insider look from someone at the center of the labor movement in one of the largest cities in the country. Followers of politics can trace the major shifts and interests of parties over recent generations. For the civically minded individual, the book can be read as a guide on how to build a coalition to accomplish meaningful change. For those with a connection to Philadelphia, it is the story of a neighborhood guy from a rowhome in the northeast, a story of Acme, A&P, Super Fresh, Frank Rizzo, Lit Brothers, the MOVE bombing, the Phillies, the Eagles, the Bulletin, and the Inquirer.

Wendell Young was a venerated labor leader in Philadelphia, one who had the somewhat radical idea at the time that unionization efforts should go hand-in-hand with civil rights gains, gender equality, and later, the anti-war movement and LGBTQ rights. Joining the Retail Clerks Union Local 1357 as a teenage part-time employee at his neighborhood Acme in 1954, Young quickly rose to leadership positions, first as shop steward, then later as president of the union.

A constant theme that emerges in the book is Young’s belief that organized labor can and should be a force for social justice. This was a departure from the traditional union approach as a bargaining force for its members but with few concerns beyond them. “It’s more than just our own conditions we need to be concerned with,” writes Young. Particularly in his early years, he leads his own union into support of the civil rights movement, including the famous 1963 March on Washington. Young’s memoir is far from an abstract argument, however, as he is always mindful to show actual effects of his efforts. A 1965 union-mandated reclassification of job titles in supermarkets led to an integrated work force as black employees were no longer relegated to custodial or maintenance jobs. At the same time, women were no longer held to a different pay scale, which in turn put them in line for different roles within the stores, including supervisory ones. Young continued throughout his career to challenge the racial divides in organized labor and in local politics, especially the Philadelphia mayoral races. His view of social justice would later expand to include a belief that war, specifically the US involvement in Vietnam, was an issue that had a direct and negative impact on the working class and that his union had a responsibility to oppose it officially. Relatively late in his career, Young re-examined his Catholic-taught views on homosexuality and grew to recognize the vulnerability of LGBTQ people in the workforce, ultimately securing through union contracts with employers protections against orientation-based firings.

Young’s memoirs include a secondary focus on local—and to a lesser degree, national—politics, specifically as the candidates supported labor or other progressive causes. Young’s writing shows a clear belief that organized labor must be well connected but not subservient to political leaders. Never afraid to buck the system, he would easily break with Democratic ward leaders if he felt their candidate was not supportive enough of unions or if they were particularly hawkish. Racism, such as what came from Frank Rizzo in his candidacy and tenure as Philadelphia mayor, was especially a deal-breaker for Young, who could not bring himself to endorse through his union the fairly labor-friendly Democrat. For readers new to Philadelphia who wonder why the City-Hall-adjacent statue of Rizzo is often a point of contention, Wendell Young makes it plain.

The book’s editor Francis Ryan states clearly in the introduction that he has taken pains to keep Young’s voice as unaltered as possible in the transition from oral interviews with Young to the writing. This gives the reader an idea of not just Young’s narrative, but of him as a person, which accomplishes two things. It keeps the reading informal and personal at times that could otherwise threaten to become a detached recounting of historical facts. Through occasionally casual language and present tense story-telling (“I’m sitting there thinking…”) Young constantly reminds you that there is a human at the center of these events, which leads to the second effect of keeping Young’s voice strong: his morality shines through. Even in the unavoidable deluge of acronyms, initials, titles, and names, there is a constant expression of heart, compassion, optimism, and goals for the working person.

A reader in 2020, a time in which it has been said that everything is political, probably cannot help but see parallels between certain events or figures in Young’s memoirs (George McGovern’s being “committed to tax reforms that would close loopholes that allowed the rich to write off luxuries … and [sponsoring] a National Health Insurance Act that would give medical care to all,” or Rizzo being portrayed as sensitive to criticism, attacking the press, using personal mockery in races, and race baiting). The main parable for today’s audiences, however, may be the story of a person who knew when to compromise and when not to, when a political candidate or labor leader could be worked with and when their approaches or goals were unacceptable. Wendell Young acknowledges his gains and losses but dwells on neither; he was simply too focused on the next need of the working class.

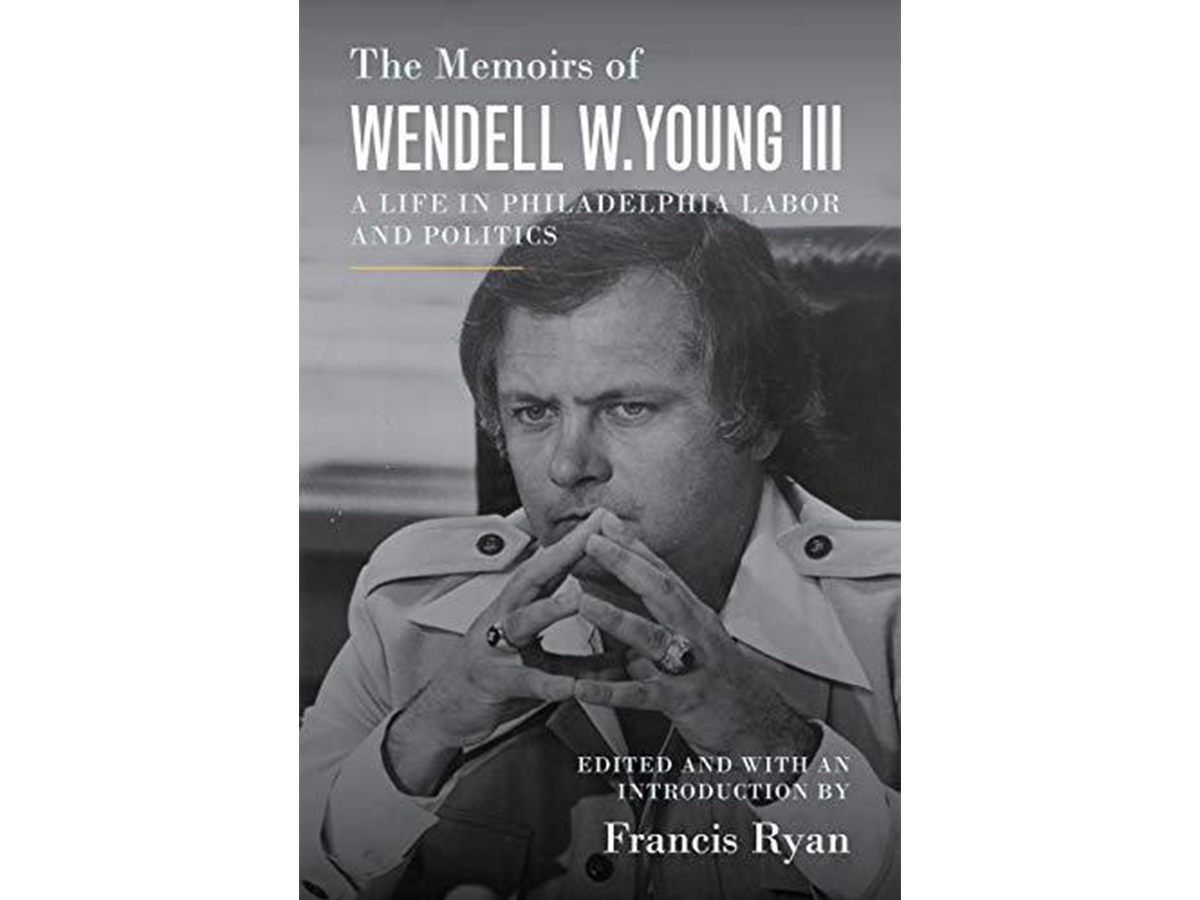

The Memoirs of Wendell W Young III: A Life in Philadelphia Labor and Politics

by Wendell W. Young III and Francis Ryan

Temple University Press

Published on June 21, 2019

306 pages

Benjamin Barnett is a full-time instructor of English as a Second Language at the English Language Center at Drexel University, as well as an occasional adjunct in the First-Year Writing Program. In addition to his instructional duties, he serves as a program manager for many of the short-term special programs hosted by the ELC, including the Fulbright pre-academic program. He conducts new student orientations for the ELC and enjoys leading tours through Philadelphia for international students.